- Home

- Kate Moretti

The Blackbird Season Page 7

The Blackbird Season Read online

Page 7

“Taylor, that’s not possible. The nights are still pretty cold. In the thirties sometimes.”

“She says she has a fire. And some kind of oil heater? I don’t know where she’d get that.”

Every other person in this county was a hunter. Schools were closed for opening day of buck season. Camping equipment wasn’t hard to come by.

“Plus, I think she skipped work. She never does that.” Taylor kicked the leg of the desk, a quiet, steady thump vibrating up Bridget’s arms.

“She works?”

“At the Goodwill. A few nights a week,” Taylor said, but with an air of confusion like a girl who’d never had a job might say.

“What do you know about her family?” Bridget asked, her tongue thick. Taylor shifted the binder in her hand and stared at the wall behind Bridget’s head.

“Enough. I don’t go there much. Her dad left, but I don’t know when. He’s a drunk. Her brother is Lenny Hamm. He was supposed to graduate like three years ago but he dropped out.” She shrugged like this was no big deal. “Heroin.”

“Heroin?” Bridget blanched.

“A lot of kids use,” Taylor said.

Bridget sighed. She thought of her tea. Her cat. She stood, grabbed her purse. “Come on, Taylor. You’re in it now.”

Taylor stood but hung back. “I should get home, Mrs. Peterson . . .”

“I’ll take you home,” Bridget said. “After.”

• • •

Bridget had never been to a student’s home. That was more Nate’s thing; he’d been invited for dinners with the baseball players, steaming plates of homemade meat loaf and mashed potatoes. Comfort food as thanks. Bridget kept a nice air of distance and she’d wanted it to stay that way.

Lucia’s house sat outside of town, away from the developments and square streets that formed “downtown” Mt. Oanoke. It stood alone, beyond the trailer park on the outskirts, over the railroad tracks, literally the wrong side. It was asphalt sided, broken in places, and the shingles were hanging. The house was grayish-brown, a noncolor, and the porch was sunken as though supporting the weight of some invisible giant. The upstairs window was broken, splintered out like a spiderweb.

Bridget stared at that window, halted at the end of a broken sidewalk, one arm outstretched protectively in front of Taylor.

“What’s wrong?” Taylor asked.

“That curtain,” Bridget pointed to the broken window. “I think it moved?”

“I’ve been here before, it’s no big deal.” Taylor shrugged. “It’s just a mess. Her family is a fucking mess.” Her hand went to her mouth and she let out a little whoop. “Sorry.”

“Should we have called first? Lucia, I mean,” Bridget asked.

“She doesn’t answer her phone much anymore, anyway. Just text, and only sometimes.”

Bridget navigated the upended concrete. The porch groaned under their combined weight. She knocked. Waited. Knocked again.

Finally, the interior door slid open, wide enough for a face, a pair of gray eyes.

“Yeah?” The boy looked like Lucia, skinny with that same shock of white hair. Lenny, Bridget guessed.

“Is Lucia here?” Bridget asked, and Lenny looked past her to Taylor, regarding her with a nod.

“No.” He started to close the door.

“Lenny, wait.” Taylor reached out, her hand on the screen door handle. “When did you see her last?”

“Uh, I don’t know. Awhile ago.” Lenny shrugged, and in doing so the door inched open. Bridget could see the living room beyond, dark and brownish. Trash on the floor. A smell wafted out the door, ripe and sour, like beer and body odor.

“Is your father here, Lenny?” Bridget asked, hiking her purse up on her shoulder, reflexively crossing her arm across her chest.

“No. Who are you?” Lenny finally asked, his eyes narrowed.

“I’m Mrs. Peterson, Lucia’s teacher. If she’s not here, have you reported her missing?”

“Uh, is she missing?” Lenny scratched his head. “Has she been in school?”

She had, of course, but Lenny didn’t know that.

“Where is she staying, Lenny, if she’s not here?” Taylor pushed past Lenny into the house and Bridget followed her, impotent.

On the inside, the smell was worse. Greasy, cloying. Bridget held her breath, looked around. The place was sparsely furnished, a couch and a television propped up on wooden crates. She craned her neck to look to the kitchen, piled high with pots and pans. As far as she could tell, the garbage had been accumulating for months.

“God, I haven’t been here in forever. What the hell happened?” Taylor turned in place, a slow pirouette. “Where’s Jimmy?”

“Who’s Jimmy?” Bridget asked.

“Lucia and Lenny’s dad.” Taylor said. “This place has always been a shithole, but not like this.” She didn’t even apologize for the curse this time.

“Jesus, Taylor,” Lenny said, coming into the living room behind them.

“Lucia said she ran away. She’s been staying in the old paper mill. When was she here last?”

It seemed irrelevant. They would just go there. Bridget hung back, trying to gauge their intimacy. They knew each other, but how well? How often had Taylor been here? Were things in Lucia’s life ever normal? Happy? She tried to envision a mother. None came to mind.

“Lenny, where is your father?” Bridget pressed. She got the feeling Lenny was avoiding the question.

“I don’t know,” Lenny grumbled, sinking down onto the plaid couch.

“You don’t know?” Bridget asked. He was probably twenty years old. Lucia was eighteen, it was hardly a concern if they lived alone. But to not know?

“He left here, drunk, months ago. I ain’t seen him since. We had a fight. I figured he skipped town. Listen, this ain’t that weird, you know. He done it before.”

“He has? When?”

“I don’t know! He don’t like what I say, so he leaves. We’re all adults.”

“What happened to your mother?” Bridget asked, and wondered about the invasiveness of the question.

Lenny laughed. “That bitch? Well, gee, now y’all go digging and y’all don’t stop. I ain’t seen her in prolly ten years. The mill closed and then she left same as him. Took him a little longer, but I guess she’s smarter. Now Lucia. Only me in this house.”

“Did you call the cops about Jimmy?” Taylor asked.

“Sure. You know what they told me? They’d put out an APB.” He let out a pfffftttt. “Do you think they care about the town drunk and his druggie kid? They ne’er found his car but I guaran-damn-tee they ne’er looked.”

“So you’re telling me that Jimmy’s gone and now Lucia’s gone and you never called the police about her?” Bridget asked, her voice slow and deliberate.

“I just figured she ran off to find him or something.” He made it sound illicit.

Bridget shivered.

“Why would she do that?” Taylor asked.

“Oh, ’cause she took care of his drunk ass. Waited hand and foot on him.” Lenny wiped a line of grease from his forehead, up into his hair, glinting and wet. “Ne’er gave a fuck about me, though. ’Cept to beat my ass.”

• • •

“Let me take you home, Taylor.” Bridget’s offer was halfhearted.

Taylor shook her head. Hard. “If you’re going to the mill, I’m going with you.” She hesitated a beat. “Even if you’re not, I’d probably go myself. I’m worried about her. There’s been something off with her. I can’t tell what.” She looked out the window. “Lenny’s bad. I’ve never seen him like that.”

“How long have you been friends?” Bridget asked softly.

“Since kindergarten. They had a mom then, though.”

“What happened to her?”

“I don’t know. She just . . . left. After the mill closed, when Lenny was still normal. I guess we were ten or so. She sent letters for a while, but Lucia was pretty pissed about it. I don’t think

she ever wrote her back. My mom takes care of Lucia a lot, feels bad for her. We had a séance once.” Taylor traced a pattern in her jeans with an index finger, avoiding Bridget’s gaze. “Maybe sixth grade? We burned everything. Her mom’s clothes, her letters, her pictures. Jimmy found us. He said he was mad, but there was no conviction behind it. I got the feeling . . .” She took a deep breath. “He was proud of her for it. Listen, she’s never been normal, I know that. She pushes into people, gets under their skin. She flies in people’s face. Sometimes I think it’s all she has. This . . . persona. But deep down, I think she’s more like everyone else than she wants to believe.”

Bridget considered this, Taylor with her Seven jeans and her Free People boots. Lucia with her black secondhand clothes. Taylor gave Lucia social credibility. Lucia gave Taylor’s bubble gum an edge.

“Okay, you can come with me, but we’re not going alone.”

• • •

Tripp Harris didn’t look comfortable. They met in the dusty parking lot of the paper mill, their cars meeting nose to nose, hers blue, his black. The redbrick facade of the mill was crumbling and the roar of the dam in the back made it hard to hear.

“Bridget.” Tripp smiled uneasily. “Nice to see you again. Although, this . . .” He spread his arm out wide. “You should let me call this in.”

“We will. If it’s anything. I promise.” She pulled her hair back from her face and lifted one shoulder. “It’s a student. If I can avoid the police, I’d like to.”

“You know, I am the police.” Tripp smiled and leaned down to peck Bridget’s cheek. “What’s the urgency?”

“I think a student of mine is living in here.” Bridget stomped her feet to get the cold out, her breath coming in puffs.

“Okay. And you are . . .” Tripp looked at Taylor.

“Taylor Lawson. Lucia’s best friend.” Taylor dipped her chin, shy.

“Another student,” Bridget said.

“Aw, Bridge, let me call it in. Take Taylor home,” Tripp said again softly. His teeth gleamed white in the purple twilight. He put his hand on Bridget’s elbow and she was reminded of the last time she saw Tripp, at Holden’s funeral, standing with the rest of the bar league softball team. Tripp had been a periodic fifth to their foursome, single and flaunting, a string of girlfriends at cookouts and barbecues. Girls, not women, merely twenty-five, perky breasted, and lean legged. A man-child with a badge.

Bridget ignored his request. “How do we even start to look?” It was four o’clock; the sun would be setting, the sky streaked bright red, plunging the mill into darkness. Close to nine hundred thousand square feet, the mill stretched out for what seemed like miles of broken windows and crumbling brick. The interior was likely to be treacherous. Bridget realized at once how stupid this was. Lucia could be anywhere. She looked at Taylor. If something happened to the girl, Bridget could lose her job, maybe her license.

“Let’s just do a quick perimeter search. If we don’t find her, we’ll call it in,” Tripp said, eyeing the pinkish sky. “But keep in mind, she’s eighteen. As long as she’s coming to school, they might not invest the time. They’re taking regular OD calls. It’s getting worse, you know? We’re a small force.”

They picked their way around the side of the mill and Tripp retrieved a mini magnum flashlight from his back pocket. He shone the light in the side windows and the beam bounced off giant spools and tables, the detritus of a decrepit industry. Aside from words scrawled on the walls in haphazard spray paint (Whore, Bitch), the place looked appropriately abandoned.

Bridget kicked a Miller Lite can and everyone jumped.

Tripp moved to the next window, then the next. He shone the light up to the second floor, then the third, but unless Lucia was crouched near a window, they’d never see her.

In the fourth set of windows, there was a crumpled red shirt in the corner, covered in dust. Been there awhile.

They moved on, Tripp leading the way, Bridget close behind. She held Taylor’s hand with one hand while gripping the back of Tripp’s jacket with the other, the slick nylon sliding between her fingertips. He smelled of cologne, and she wondered if he had a date later.

“Bridge, I see something.” Tripp stopped short and Bridget ran into the back of him, pulling Taylor with her. The light from the flashlight glinted off something metallic.

A kerosene heater.

Taylor dropped Bridget’s hand and ran. Toward the water, the dam, that loud rush. In a panic, she yelled, “Lucia! Lucia!”

Tripp chased her. “Taylor! Come back, she won’t hear you!”

One side of the double-door entrance to the mill had been kicked down years ago. Only one door hung creakily from a twenty-four-inch hinge.

Tripp stopped and swung the light between the interior and the outside, where Taylor had run, indecisive. The lure of Lucia won out, and he turned into the corridor of the concrete building.

“Lucia!” called Bridget, her skin alive, crawling. “She’s not out there. She wouldn’t hear you anyway.”

Taylor stopped, her back to the mill, staring in the direction of the dam, the mist collecting in her hair. She shrugged and turned back, pushing past Bridget and inside, after Tripp. Bridget followed.

Dust and beer cans, garbage and plastic bags, clothes, the makings of a campfire littered every room. It was a teenage party haven.

They got to the room with the heater, which was off. There was a small black backpack, the zipper tied with a rainbow braid, that Bridget recognized as Lucia’s. A journal, the pen between the pages like a bulbous bookmark.

Taylor came up behind them, breathing hard, her face red and sheened with sweat.

“Any luck?” Bridget asked, but Tripp already had his cell phone in hand, dialing.

“Nothing,” Taylor said.

Lucia was gone.

CHAPTER 8

Alecia, Saturday, April 25, 2015

“Do you think an affair with a student is something to laugh about?” Alecia stood in the living room, her hands on her hips. Gabe was in bed, finally asleep, and the story of the day came out fast and jumbled. She’d never had a poker face, never could play her cards close to the vest. The truth spewed out.

“It’s so ludicrous, that’s all.” He cocked his head. “You can’t believe it?”

“Tell me why I shouldn’t.” Alecia shook the single sheet of paper—the bank statement with Deannie’s Motel—in front of his face. He cupped his forehead and stared at it.

“I did buy a hotel room for a student. Do you know Lucia Hamm? Have I talked about her?” He sat in the chair, choosing to avoid the couch where Alecia perched on the edge, brittle and nervous. “She’s troubled. I don’t know much about her home life, but she called me a month ago for God’s sake. Said she was sleeping in the paper mill. It was forty degrees at night. But she’d run to Honesdale and asked if I could meet her.”

“That was the day of Gabe’s kindergarten meeting.” Alecia tried to keep her voice calm. “You couldn’t just tell me?”

“Why? You’d flip shit, Alecia. You count every penny in this goddamn house, every single thing is budgeted, we eat generic oatmeal, like I can’t even have Quaker Oats, and you want me to tell you that I’m spending an hour’s worth of Reiki therapy on a random girl’s hotel room for one night?” His voice edged up; he was getting pissed now. “If I told you I spent that, I’d have heard about it forever.”

“Why there? Why Honesdale?” It felt illicit, like a tryst kept away from the community.

“I don’t know why!” Nate palmed both knees, the printout fluttering to the ground. He leaned forward, puffed out his cheeks and blew, like blowing out candles. “I didn’t ask many questions. I tried to keep her calm. She was crying, hysterical. I told her I’d help her for one night, and then told her I would call Tripp to get her the number of a shelter. She’s not a minor. The foster care system is useless to her.”

“How’d she have your number?” She yelped then, an aha, caught you.

“All the kids have my number. I give it to them.” He said this dismissively, waved his hand in her direction.

She ignored it. “So then what? Did you go back?” Her questions were a freight train, ramming into the front of her skull. She couldn’t ask them fast enough.

“No. She freaked out. Said that Tripp was looking for her. Officer Harris, she called him. That for some reason, Taylor and Officer Harris were together at the paper mill, going through her stuff. She was afraid of getting arrested.”

“Arrested? For what?” The entire story felt made up; nothing made sense.

“I don’t know! She just said she ran away, that she couldn’t trust anyone anymore, and would I help her? I said I would for one night, then she needed to go to a shelter. I asked her what happened at home but she wouldn’t talk about it. Only that she couldn’t live with her brother anymore.” Nate cleared his throat, his foot tapping. “This is stupid, Alecia. You can’t believe any of this. It’s like . . .” He searched for an analogy and came up empty.

“Aren’t you worried? This reporter is spreading this story, you could lose your job. Don’t you care?” Her voice pitched into a screech. He’d put their whole family at risk for a girl and a motel room. For what? What would happen to them if Nate got fired? “An affair with a student is a big deal. People get fired on the accusation alone. It’s rape, Nate.”

“Alecia!” He barked, looked around like someone could have heard her say the word. “If the story is about Lucia, she’s eighteen, it’s not rape.”

“Oh my God, that’s your thought? That makes it better?” Alecia tangled her fingers in her hair, almost laughing, and stopped. “This was almost month ago,” Alecia said. “Why now? What is this reporter talking about, then? Who else knows about your motel room?”

“It’s not my motel room, Alecia. Knock it off.” He stood up, walked into the kitchen, opened the fridge. Alecia heard the pop of a beer, the last indulgence she’d let him keep. His case-a-week habit was getting expensive, though.

“We can’t afford to buy this much beer all the time.” She stood up, followed him into the kitchen. She knew it wasn’t the time or place, but the words popped out of her mouth before she could stop them. She stopped herself from continuing, if we’re going to also be subsidizing runaways. If no one around here is going to have a job. They’d fought about her nasty fighting for years, her acerbic tongue, quick as a snake’s.

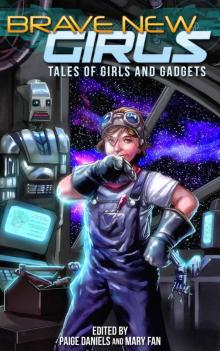

Brave New Girls: Tales of Girls and Gadgets

Brave New Girls: Tales of Girls and Gadgets The Blackbird Season

The Blackbird Season